20

COROMANDEL LIFE

SPRING 2013

Drones, vital role in

continuation of the colony

Numbering rarely as many as a thousand and

making up about 5% of the population of the

colony, male bees or drones are larger than

the unfertilised females, having developed in a

slightly larger cell than female worker bees.

Adult drones have wider, rounder bodies than

workers and, like all male bees and wasps, do

not have stingers. They are identified by huge

compound eyes that meet at the top of their

head and an extra segment in their antennae.

Drones have the single function of mating with

a new virgin queen and, boy, are they high

maintenance! They must be nurtured and cared

for by the female workers. Mating happens as

much as a mile away from the hive, on the wing

about 2-300 feet above ground. The drones

large eyes come into good use spotting the

virgin queens on their nuptial flights.

Unfortunately, the sex life of a drone is not a

happy one. Mating with the queen means the

end of life – their reproductive part has a barb

which causes parts of the body to be torn away

after mating. The drone then falls to its death.

After the period of mating is concluded and

the nectar production season ends any drones

remaining in the hive are unceremoniously

evicted from the colony by the workers. This

reduces the numbers of feeding members to be

supported over the leaner winter months. We all

know the blokes are often the biggest eaters!

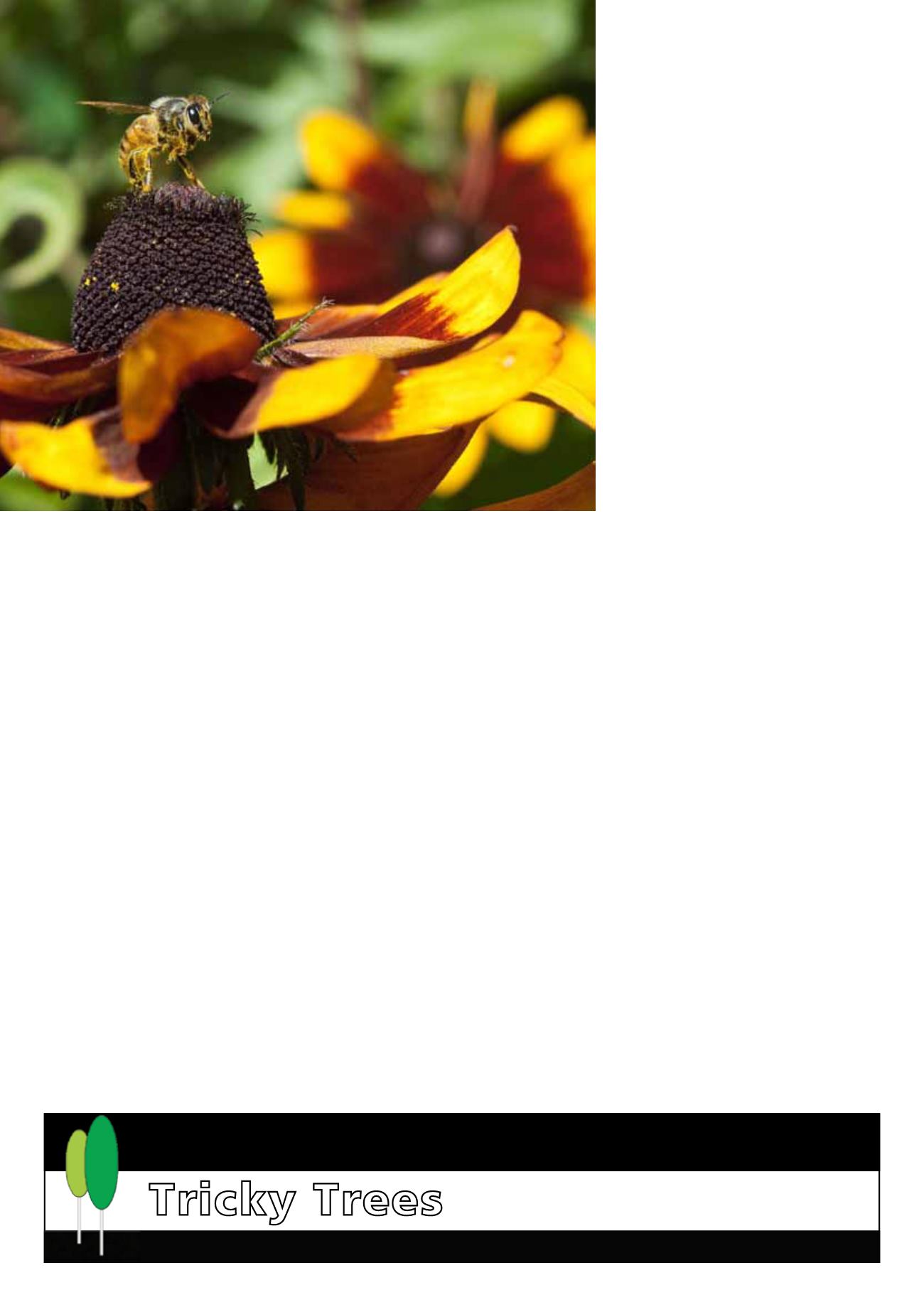

Out in the field finding

gold: The female foragers

The sterile female foragers are the true workforce

of the colony. There’s no time to protest about

working conditions! While still young they

babysit and feed the baby bees but once mature

they spend most of their life on the wing in a

collection role, gathering the raw ingredients of

honey, pollen and nectar, from flowers.

They have a blunt triangular head with three

eyes, one of which is visible on their forehead

and two compound eyes. The antennae are

divided into 11 segments and supply the bees’

senses of touch and smell. The proboscis is

used for sipping water honey and nectar and

curls back under the head. Their feet have

pronged claws for gripping onto flowers. The

pollen baskets are on the rear legs.

They work tirelessly to keep the hive clean,

make honey, royal jelly and beebread to feed

larvae, produce wax, cool the hive by fanning

their wings, shape and form the cells of the

8-sided honeycomb, the crib into which the

queen lays the eggs. They also guard the hive

and feed and care for the queen and drones. A

woman’s work is never done!

Beekeepers can ensure more forager bees are

born by returning the waxy comb to the hive,

or by melting the wax and creating a “honey

comb” wax sheet, imprinted with the size of the

foragers’ cells. The foragers don’t click onto the

ruse and continue their waxy buildup of even

Tricky Trees

PROFESSIONAL LOCAL ARBORISTS FULLY INSURED

Tel: 021 240 9909

crown reduction • tree felling • thinning • stump removal • consultancy

difficult removals • hedge & shrub maintenance • waste recycling

more forager cells so more foragers are born,

and thus more honey is produced by each hive.

THE BEE DANCES

Bees communicate in an extraordinarily detailed

way. On their return, scout bees run on the

surface of the comb, indicating to the others

the direction others must fly to locate the flower.

The scouts then perform a circular dance if the

flower is within about 100 metres of the hive.

Stimulated by the dance other bees go out in

search of nectar. The dancing bee has the scent

of the target flower on its body and has left a

scent clue on the flower.

Ever wondered where the term ‘beeline’ comes

from? If the flower is further away, the dance

is like a figure 8. The speed of the dance and

the rate at which the scout wags its abdomen

communicates the exact location of the nectar.

So much information is communicated in the

dance that the bees are able to make a ‘beeline’

for the nectar.

Another dance tells of potential new homes

when the hive is overpopulated. The old queen

then moves out with about half of the colony,

leaving it to a new queen.

WE NEED THE BEES

Although bees may not need us, we do need

them. And always have. Bees were first

domesticated in Egypt around 2400BC and

speaking at a TED conference in Boston in

2012, 30 year old, Noah Wilson-Rich, called

America’s sexiest bee scientist, said bee

drawings have been found in caves dated

13,000 years ago.

In an earlier TED speech in 2008 Dennis van

Engelsdorp made a ‘plea for bees’. “Tasting

honey for the first time is just sort of nectar from

the gods. They’ve always inspired us. I also

think it’s connected with our youth — you know,

running barefoot through a meadow, getting

stung in the toe… is a rite of passage. And I

think we all understand at some level that if that

can’t happen anymore, that we’re diminished.”

With our reliance on agriculture and horticulture

in this country the simple honey bee plays

an essential role in our economy. NZ earns

over $80 million annually in honey from the

9-12,000 tonnes produced, almost half of

which is exported. Income is also generated

from domestic sales of honey, beeswax and

exporting actual honey bees.

Bees also perform the function of pollination

of agricultural plants such as clover, sown as

a nitrogen regenerator for pasture, providing a

nourishing foundation for our wool and meat

producers.

Although many countries are fighting off total

bee colony collapse, our diligent New Zealand

beekeepers have managed well. A recent report

stated that there are currently 450,000 managed

hives, up from around 300,000 in 2005.