EARLY

GOLD

G

old mining in the Coromandel began in earnest – after some fits

and starts - in 1852 when the Auckland Provincial Council offered

a £500 reward for a ‘payable’ gold find on the north island.

Enter one Charles Ring (born 1816) who came to Auckland via Australia

where he had opened a store which sadly burned (one of many business

disasters he survived). He then tried his luck in Auckland, where he

managed to informally purchase a few farms for raising sheep from

a local Maori chief. With his brother Frederick, they imported several

hundred head of cattle, but that venture did not work out as they could

then buy no pasture land for the herd.

In 1849, news came of the California gold rush, and they sold the cattle

at a loss and sailed off to seek their fortunes. After a successful stint of

prospecting, Charles bought goods for opening another store, but he lost

that stock in a shipwreck.

He and Frederick booked passage back to Australia, but ill fate visited

once again. Their ship tangled with a reef off Fiji. The shipwrecked

passengers (many fellow prospectors) survived, trying then to complete

the voyage in an open boat with little provisions. Luckily, an American

whaler caught sight of the stranded crew, rescued them all and

transported them back to familiar territory, Auckland.

THE RINGS GET A FOOTHOLD IN THE COROMANDEL

The Rings managed to secure land northeast of Coromandel town,

and opened a kauri sawmill on Kapanga Stream. By this time the

Coromandel’s kauri timber operations had already been in overdrive for

decades from the many visiting timber-harvesting ships (such as 1820

arrival of the HMS

Coromandel

), and European settlers from the 1830s.

Many local Maori were already working for the newcomers – growing

potatoes and peaches for them, or trading fish and game.

Because of their experience in the California gold fields, the Ring

brothers took notice of the area’s geology and realized it had gold

potential, not just in their stream, but through the promising quartz veins

found through most of the Coromandel territory.

Prospecting expeditions through Maori land were undertaken. Some

Maori tribes were welcoming and gracious, but others attacked the

gold seekers. Escorted by a European settler who had experience

with the natives (and presumably because of the brothers’ legendary

graciousness), they managed to traverse a lot of territory ‘just looking’

for signs of quartz veins and gold in the alluvial streambeds. Charles

became especially proficient as a Maori linguist.

In 1852, Auckland Provincial Council offered a £500 reward for a

‘payable’ gold find, and Charles Ring was ready with samples from their

Kapanga Stream area which was fed by Driving Creek. The origins of this

name came from the practice of using a header or ‘driving’ dam to store

felled timber. When the dam was released, the kauri logs travelled down

the ‘driving’ creek to McGregor Bay at Coromandel Town.

The council members dutifully trekked three miles upstream to the Ring

brothers’ mill, and their find looked promising. However, because of the

complexity of the Maori land ownership, not much of their reported finds

were actually workable yet, thus they were paid only £200 reward money.

The government did settle mining licensing fees with the Maori for the

‘Crown’s Kapanga block’, and it was not long before the area was

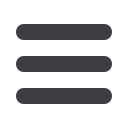

Early gold mining meant hard work. The simplest method was panning the stream’s

gravel bed for flakes of gold. Easy pickings for first-comers. Next was the use of a

sluice box, where gravel and sand were shoveled into the top grate where the smaller

bits would be washed over the lower trough. The heavier gravel and gold flakes would

lodge against stick barriers called ‘riffles’. In the longer sluice trays, gravel was shoved

right into the trough and larger rocks removed by hand.

Note the man rocking the sluice box is using a simple water scoop. An improvement

was to instead direct stream water through a pipe or wooden channel, and to use the

longer trays. The pan came out later to swirl away the lighter sand, leaving just the gold

flakes. Often men would merge their claims and work as a team, as is seen here.

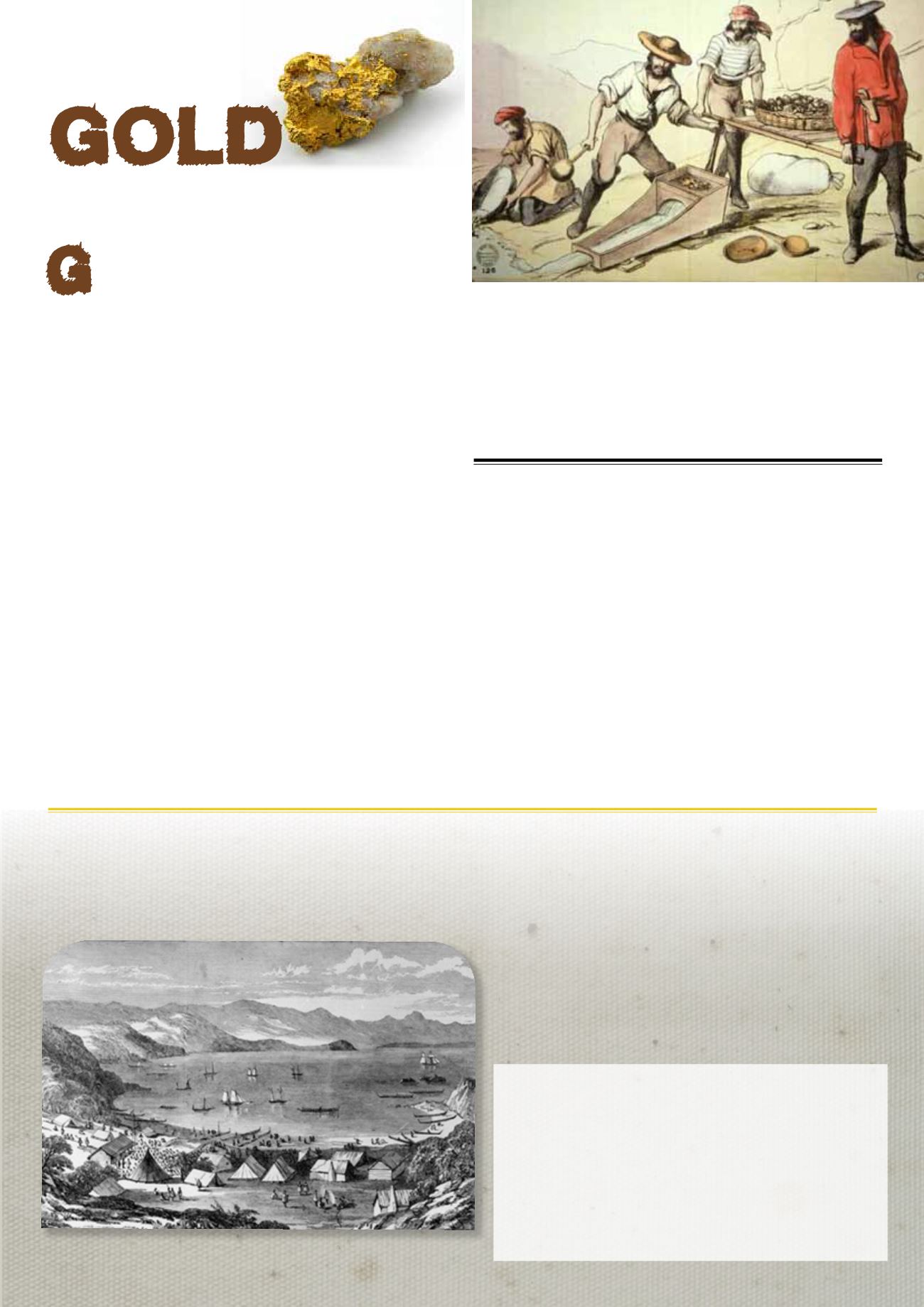

MEETING WITH THE

MAORI FOR THE 1852

GOLD FIELD AGREEMENT

Within one month of the land use agreement, over 3,000 men arrived on the

Coromandel field to mine for gold, but the rush lasted just a few months.

L

and use agreements for logging, gold mining, and

pastureland between the Crown and Maori tribes were

made in stages over decades. Some individuals, were also able

to secure rights for land use or for outright purchase.

The Ring’s Driving Creek discovery cash reward was not fully

honoured because there was not (yet) Maori agreement for

permission to mine in vast areas.

However, in October of 1852, Lieutenant-Governor Wynyard

met with Maori chiefs at Coromandel Harbour, and Heaphy

illustrated the variety of Maori longboats and European ships

assembled.

Showing NZ’s early history depends on artist’s sketches and

watercolours, in this case those of artist/surveyor Charles

Heaphy.

(continued on page 15)

Details of Hauraki Peninsula land use agreement

of

November 30, 1852 between

the Crown and Maori landowners.

Area: Between Cape Coleville and Kauaeranga

(Shortland, Thames).

“Under this agreement, the Government pledges itself to pay

per anum to the Maoris: For less than 500 men digging £600,

for 1000 to 1500 men digging £1500, for 1,500 to 2,000 men

digging £1500: and in addition, 2s for each miner’s license

issued. To meet this and other expenses, a tax of £1 10 s per

month per man was imposed on the miners.”

WWW.COROMANDELLIFE.CO.NZ13

The Ring brothers and the

discovery of Driving Creek’s gold