O

nce gold was discovered, and

negotiations completed, the Thames

area’s population exploded. Now the

largest town on the Coromandel, Thames was

once the second largest in NZ, after Dunedin. In

1871, it was larger than Auckland by 4000.

Early colonial settlers included C.M.S.

missionaries, who established their first

mission station inland near Puriri in 1833.

They soon moved their station nearer the Firth

to an area called Parawai in the hills edged

by the Kauaeranga River – not far from the

Kauaeranga Pa and presided over by the savvy

Ngati Maru rangatira Taipari.

This area – Kauaeranga to Maori (later called

Shortland) – had seen some European influence

with traders visiting the area. Maori had planted

orchards and gardens, and traded produce with

settlers in Auckland.

Chief Taipari, born Hauauru, adopted Christianity

and was baptized Te Hotereni. When Taipari

(senior) died in 1880, the son Hauauru Tikapa,

baptized Wirope Hotereni (after Willoughby

Shortland the first Colonial Secretary for New

Zealand) took over his late father’s role in the

tribe’s business affairs.

James Mackay had been commissioned

by Government in 1864 to secure peaceful

relations with the tribes in the area. He was

successful in persuading the local hapu to open

the land up for mining after several visits. We

might infer that the Taiparis, father and son,

were positively disposed to pakeha since they

had both been baptised as christian – hence

the ready friendship with Mackay in the difficult

task of persuading local hapu to open the land

up to mining.

Te Hotereni had arranged for Maori prospectors

to seek gold on his land and actively

encouraged prospecting. With the finding of

gold in the Karaka stream, and after protracted

negotiations, the goldfield was proclaimed

open on 1 August 1867.

THE GOLDFIELD OPENS

BUT NEEDS A TOWN

News of the gold strike quickly reached as far

afield as Australia and England. Thousands

of hopeful miners – one report counts 11,000

miner’s rights issued – swarmed into the tight

little goldfield.

Quickly a settlement of Maori

whare

, rough

wooden shanties and tents sprang up. Miners

and labourers lived rough. Stores were set up

in tents. The Maori’s peach tree orchards were

soon felled for firewood, and the hills behind

the fledgling settlements were also quickly

denuded of vegetation. Hundreds of eager

prospectors pegged out their claims.

Because it was easy to land goods and people

at the shallow mouth of the Te Waiwhakuranga

River, Mackay (aided no doubt by the eager

Taipari, soon to be colloquially known as the

Squire of Thames) set up his Government office

on Grey Street, and laid out the township.

The Shortland Wharf was quickly built. Captain

Butt opened his Shortland Hotel, leading the

way for a spate of shop and house building, all

of which was supervised indefatigable Mackay.

SHORTLAND DEVELOPS

Governor Sir George Ferguson Bowen (visiting

in April 1868, only a few months after being

sworn in) wrote a report to the Colonial Office

in England: “There is one peculiar and very

interesting and suggestive fact connected with

the town of Shortland, viz., that it is arising on

ground belonging to the influential Maori chief

Taipari. He declines to sell his land, preferring,

with a view to its rapid increase in value, to

let it in lots on building leases.... He employs

Europeans to survey and lay out roads and

streets and to construct drains, culverts and the

like.” He estimates Taipari’s income from leases

and rents to be

£

4000 a year.

An upbeat description found in the “Thames

Miners Guide” in 1868 states: “The township

of Shortland is exceedingly well laid out, the

streets are wide and very numerous, the houses

are substantial, and in Pollen Street tolerably

uniform. This is the principal street and it can

boast of containing the Court House, Post

office, a Custom house...four banks, a theatre,

five hotels, five eating houses or restaurants,

SHORTLAND

AND ITS FOUNDERS

BY RU S S E L L S K E E T

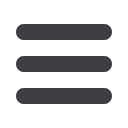

News of the goldfields reached England, where an engraving of

Shortland was featured in the

Illustrated London News

, Sept.,1869.

In this 1868 satirical cartoon, James Mackay, the

‘Thames Autocrat,’ addresses concerns of angry

miners. It is assumed that the woman seated right

is his wife, Puahaere, not only a Chieftainess of

Ngati Paoa through her mother, but King Tawhiao’s

daughter as well.

The Making ThameS

C

aptain Cook reconnoitred the inland areas along the Waihou River in

November of 1769, and was impressed with the flat navigable river,

and the expanse of Kaihikatea trees he thought suitable for masts and

spars. He named the estuarine area the Firth of Thames because of its

similarity to the River Thames estuary in his homeland England.

Nearly a century would pass before gold was discovered in this placid

region, a discovery that would change the face of the land forever.

TAIPARI & MACKAY ~ THE MEN BEHIND THE TOWN

(continued next page)

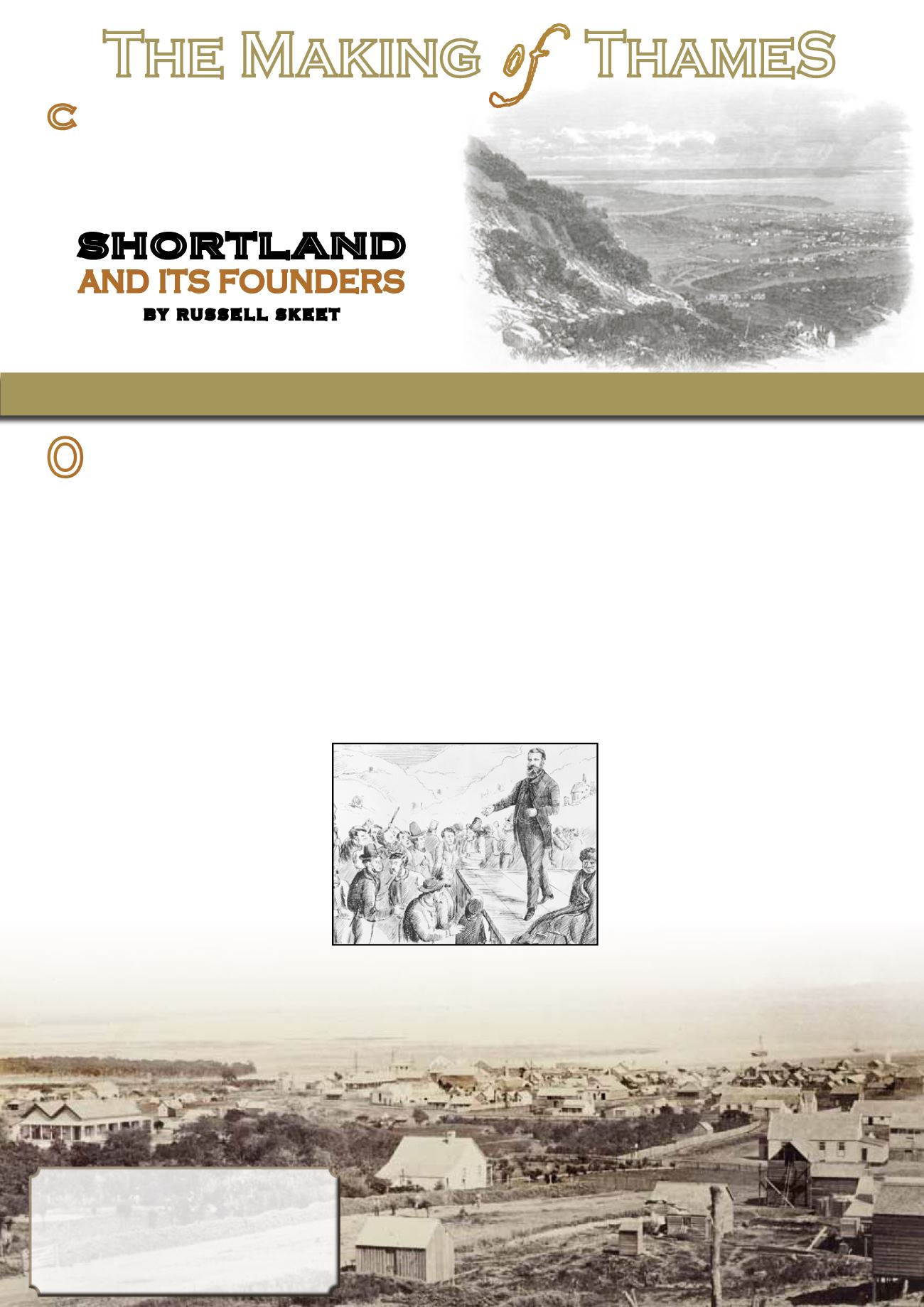

View of Shortland from the Hape Range.

James Mackay’s large home with veranda is above left.

The Kauaeranga River is in front of the row of far trees;

Shortland Wharf, showing three masts, is at its mouth.

Buildings in the wharf area include Stone’s timber mill,

the Court House, Butt’s Hotel and Theatre, and the dense

knot of business premises centred on Pollen Street.

Punch or The Auckland Charivari, 1868

21

Photo: American Photographic Co., 1869 1876, Auckland. Te Papa (O.031351)