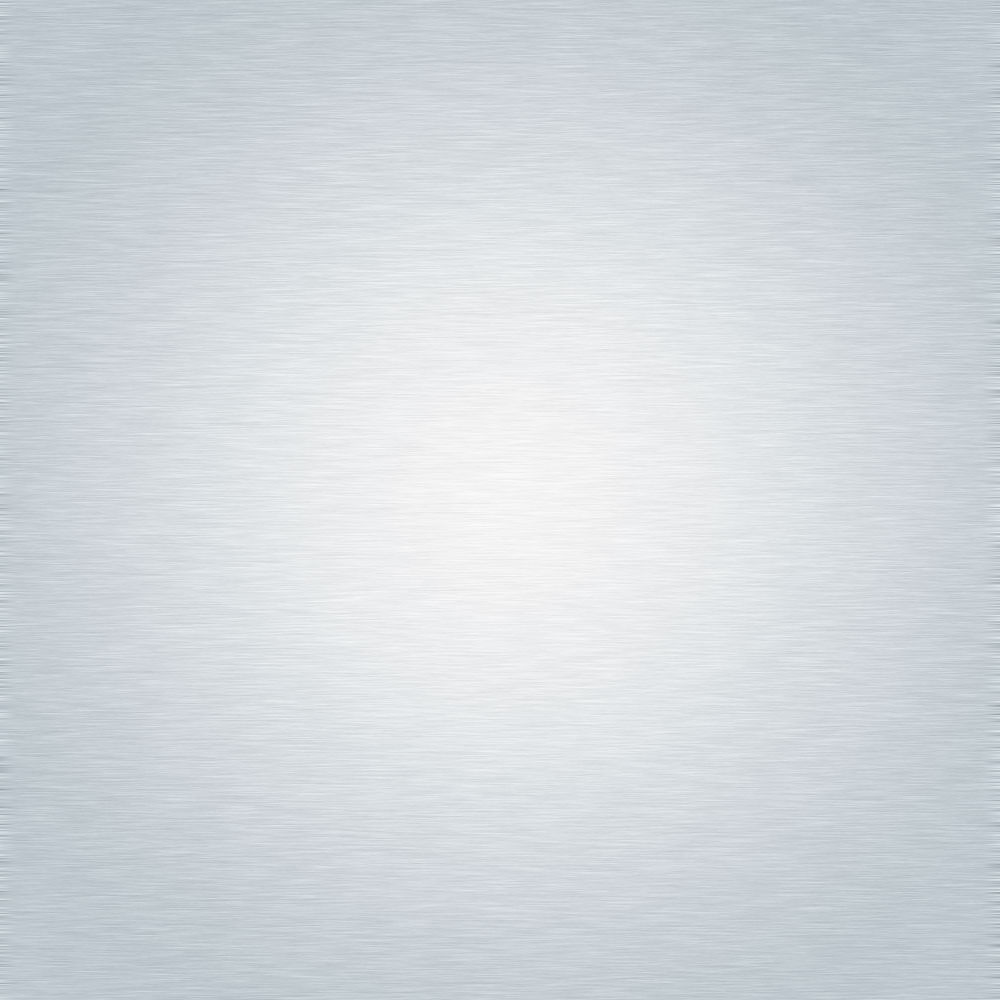

The cliffs around Anzac Cove were steep, rocky and

crumbly, covered in either sandpits or with shoulder

high shrubs. ANZAC forces dug into a cliff; improved

sandbagged trenches followed. This image captures

the challenging conditions. It is incredible that they

were able to succeed in making meagre advances

with the enemy above firing down on them...or

straight at them once they dug in on top.

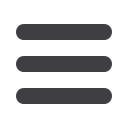

Below: Supplies pile up on the cove’s narrow beach.

Churchill has his go at the Dardanelles

Churchill’s well-armed navy fleet (now including

submarines) from Britain and France had

inflicted heavy damage to Turkey’s fortresses

protecting the Dardanelles, but these could not

be fully captured by the battleships. Mines also

claimed several ships and damaged others.

Instead of pressing forward, Churchill paused,

and sent for foot soldiers from the British,

French, and the now handy ANZAC forces in

Egypt. Meanwhile the Allies benefitted in that

Turkey’s own use of their channel was stymied.

It was proposed that the ANZACs would land

mid-peninsula on the Aegean Ocean side of the

Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey, and push across

its ten mile width. The Brits would attack the

southern tip and push north. French troops

would attack on the land across the strait, near

the ancient city of Troy. The hope was that the

Turkish forces would be defeated, expelled and

the Allies would control the shipping channel

itself and the land surrounding it. Then, on to

take Constantinople…

The ANZAC forces land on Gallipoli

In the darkness of early morning on April 25,

waves of Aussie and then NZ troops were

rowed ashore from troop carriers, but sadly

they landed a mile off target, at a small cove,

later named Anzac Cove. This was a narrow

exposed beach backed by steep scrub-covered

cliffs, its ridges topped with Turkish snipers.

This landing and defence of the beachhead

proved to be a bloody and expensive conflict

with significant loss of lives. That first day, over

650 Aussies and 147 Kiwis were killed. The

Allies’ hospital ship at the cove accepted over

550 casualties that first day and the ANZAC

nurses seemed to share one sentiment: “This

was not what they signed up for.”

Many ANZACs were shot without even having

placed a foot on the beach; in the boats or

while frantically wading ashore, under fire from

an enemy with the advantage of concealment,

height and proximity. The Turks (numbering

initially only 200) were afforded a perfect

defensive position and suitable range from

which incoming soldiers could be picked off.

However Aussie and NZ troops (each carrying

40 kilos of gear), supported by firepower from

the ships, bayonetted and clawed their way up

the steep terrain, pushing back defenders and

dodging bullets. Reinforcements landed, and

those who made it up the cliffs struggled on,

eventually capturing several ridges, and kept

pushing forward until the Turks received their

reinforcements of men, arms, and ammo.

The light unit of Turkish soldiers, who took the

brunt of the attack, ran out of ammo. They

were retreating, but were ordered by their

commander, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk: “I do not

order you to fire, I order you to die.” They stood

their ground, with only bayonets, and died until

reinforcements arrived.

Ultimately, the ANZACs held a half mile of ridge

territory before being stopped, a line that did not

move much in the stalemated fighting to come.

Gallipoli drags on...miserably

Both sides dug into deep trenches – in places

only 10m away from each other. The ANZACs

also dug tunnels to move supplies and evacuate

the dead and wounded. They fought with valour

– through exhaustion, disease, malnutrition,

injuries and the frustration of the stalemate. Many

dead comrades rotted atop the ground in No

Man’s Land, filling the air with stench and swarms

of disease-carrying flies. Countless bodies were

never recovered nor given proper burial. This was

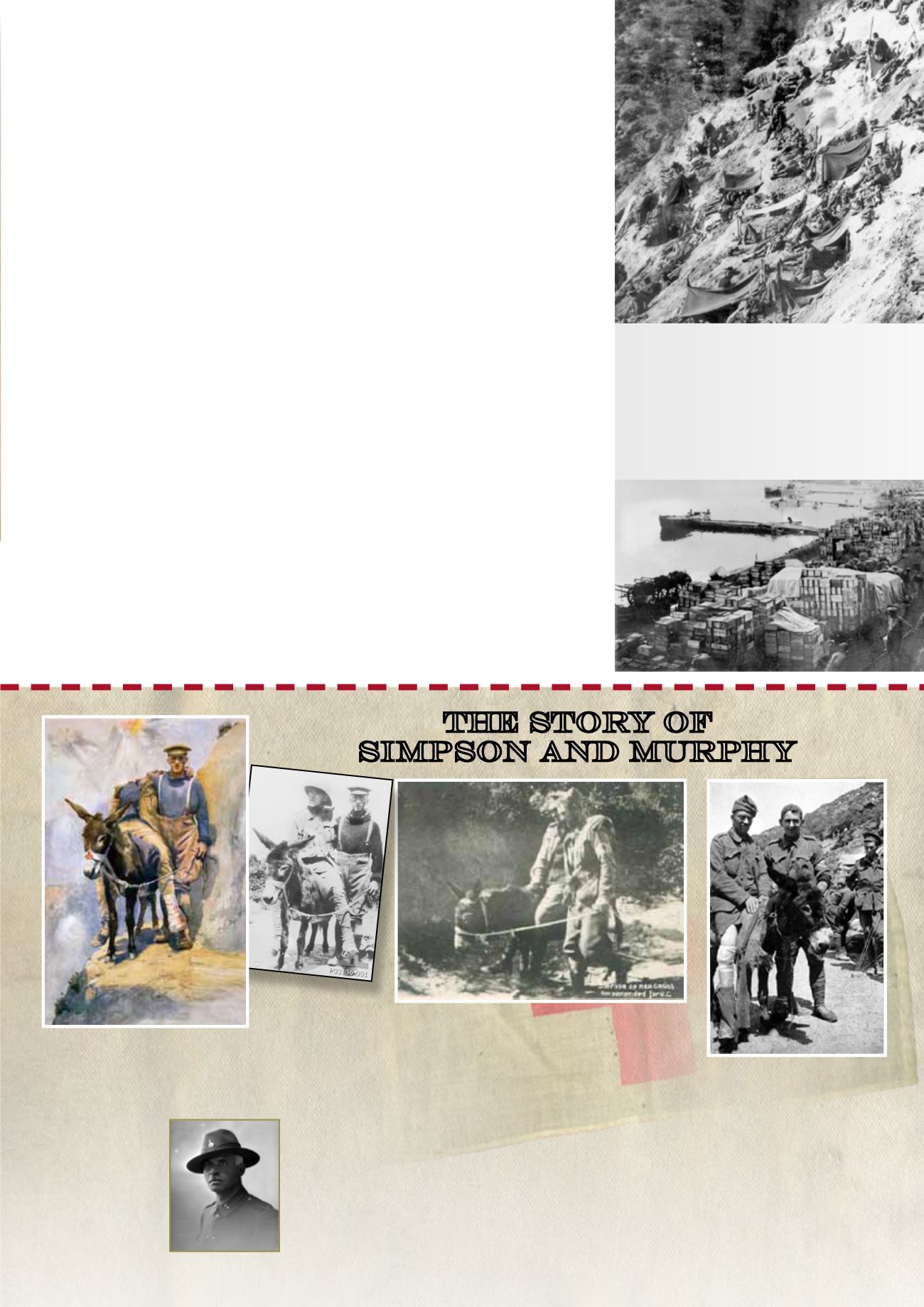

The story of

simpson and murphy

The actual

John Simpson

evacuates a

wounded

soldier (also at

right).

English born John Simpson Kirkpatrick joined

the Aussie armed forces as ‘John Simpson’, and

was assigned to the ambulance corps.

At Gallipoli he commandeered a donkey, referred

to as ‘Murphy’ (aka Duffy or Abdul) to handle

the steep terrain. It is said that together they

evacuated over 300 wounded soldiers over the

next 24 days, tirelessly working day and night,

often under heavy gunfire.

The stalwart brave pair became a mythic

inspiration to ANZAC troops, but on 19 May,

1915 a bullet found him. He was held to

represent all the finest qualities of the ANZACs,

in particular the stretcher bearers. Dead at

age 23, yet his legend lives on through this

art poster, several books and statues in both

Australia and the UK.

One book,

Simpson and his Donkey

, by Mark

Greenwood, included the little known story of

how, without realising it, Simpson had actually

rescued a childhood friend.

Simpson has yet to be awarded the Victoria

Cross...though Murphy was honourably

decorated.

continued next page

NZ war artist Horace Moore-Jones,

wounded at Anzac Cove, returned

home to create over 80 watercolours,

including the well known

Simpson

and his Donkey

, (above left), which

inspired admiration

for the entire corps.

An ironic twist is that

the painting was

actually done from a

photo of Simpson’s

replacement, Waihi

born, Private Richard

Henderson (above

right).

WWW.COROMANDELLIFE.CO.NZ11

Horace Moore-Jones

Legendary Heroes of Anzac Cove