WWW.COROMANDELLIFE.CO.NZ

WWW.COROMANDELLIFE.CO.NZ

11

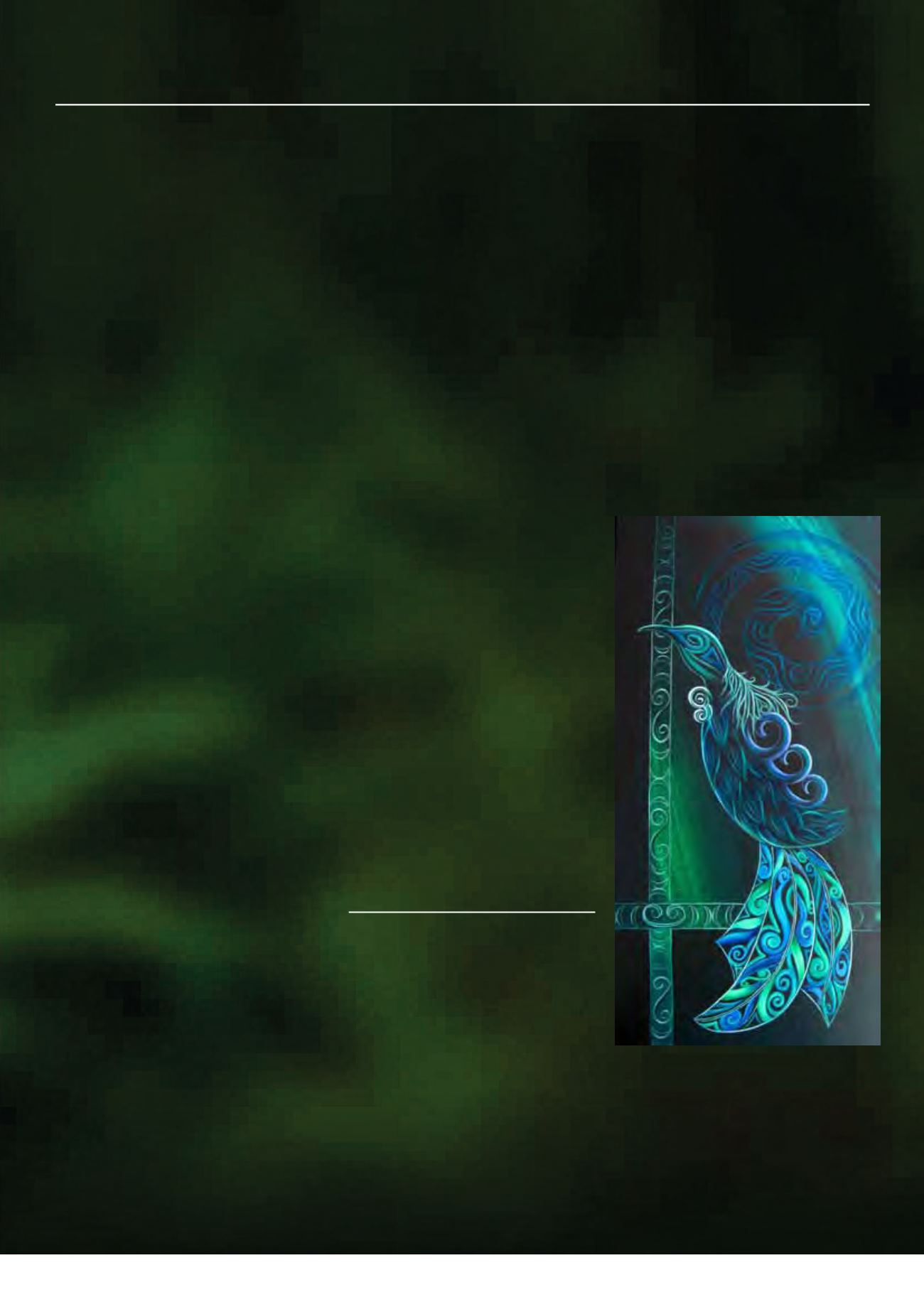

Tui Rua

by Reina Cottier.

She says about this amazing bird:

“The tui, majestic and proud,... a curious, highly

intelligent bird, is fascinating to watch, almost

letting you into their world – swooping, diving,

sitting oh so close,,... but then, protective,

fierce, swift,... and away. Like two birds in

one, as is their song, deep guttural clicks and

clucks, and then the beautiful melodic song

from another world.”

A small waterfall

on the Whangamarino Stream

near the Waikato railway is named “Te Ako-o-

te-tui-a-Tamaoho”, meaning ‘the teaching of

Tamaoho’s tui’. It is the place where Pouwhatu,

chief of Ngati Tamaoho of the Waikato area,

took his pet tui to teach it how to talk. The

name recognises both the effort of the man,

and the cleverness of the bird.

Maori believed that tui learn best when

surrounded by the sound of a waterfall. The

steady noise of the water created a sound

barrier, ensuring the bird wasn’t distracted and

would hear only his master’s voice.

Over many long days Pouwhatu taught his bird

to speak. The bird became a prized pet of the

tribe, and could recite karakia (prayers), songs

and several long speeches.

Tane-miTiRangi

Another tribe, Ngai-Tauira, also owned

a very remarkable tui which was said to

possess more than human intelligence.

Tane-mitirangi

not only learned to repeat

the most powerful karakia,

but was believed

to possess special spiritual abilities,

bewitching others on command.

This greatly

prized bird was coveted and eventually

stolen by another tribe. Discovering their

loss the Ngai-Tauira pursued the offenders

and many were slain in the battle. The few

survivors fled to Hawkes Bay.

A children’s book,

Tane Miti Rangi, te manu

korero

, tells the fate of this sacred bird, who,

with his wisdom and prayer helped provide

for the people of the Ngai-Tauira tribe.

TWO TaLKing TRiBaL Tui

R

ecent studies indicate that our native

songmaster is actually one of the most

intelligent birds on the planet. And, as a

delightful part of our daily lives, could the tui

even be beating out our national icon – the

kiwi – to be our most beloved bird?

Easily recognisable, it appears fundamentally

black, yet the feathers move through a

spectrum of iridescent colours – indigo,

purple, blue, turquoise, green and blue with

two white tufts of feathers at their throat

and a distinctive cape of white feathers over

the top of its wings giving it the cloak-like

effect – all a challenge for artists to capture

as the qualities and light of the feathers are

constantly changing.

These reminded early European settlers of the

English clergyman, dressed in black cape with

a white neck scarf, leading to its name, the

‘parson bird’. The English parson was often

said to have a beady, watchful eye, which the

tui also appears to show when he’s monitoring

you from his vantage point in a tree!

SINGING UP A STORM, AND TALKING TOO!

The musical range of tui is unlike any other in

our forests and suburbs. It fills the landscape

with a depth of different tones and sounds,

often beyond the range of the human ear, all

made possible by their ‘double’ voice box. An

Auckland study into the native call of the tui

has revealed its song ranks as one the bird-

world’s most complex.

Their intelligence and ability learn new sounds

allows them to continually adapt to the

changing sounds of their environment. Master

imitators, they are able to copy the human

voice, cell phones and other birds’ songs.

Studies show their calls vary from area to area,

like a dialect, as well as between seasons and

sexes. Tui sing in our days’ dawn and are often

heard trilling well into dusk. Unlike other birds,

they are known to call and sing at night too –

particularly around a full moon.

Early Maori trained the Koko or Poe (as they

called tui), to imitate the call women made to

bring visitors onto the Marae. And some were

even taught to recite speeches (see below).

The bird was highly regarded by Maori, often

kept as pets in cages. They were featured in

many old stories, and several gained such

notoriety they were fought over. It was said that

on one occasion a talented tui was taught a

speech to welcome Sir George Grey, governor

of NZ, onto a marae.

Alas, both settlers and Maori ate tui too, which

contributed to their decline. In 1773 on his

second voyage here, Captain Cook described

the tui as “not more remarkable for the beauty

of its plumage than the sweetness of its note.

The flesh is also most delicious and was the

greatest luxury the wood afforded us”. And,

horrors! The bird’s skin was also used to line

ladies hats! Thank goodness for a law change

in the 1880s banning the hunting of tui, or we

might not enjoy them now.

While not endangered, tui numbers have sunk

to dangerous lows at times in our history. The

tui’s eggs (typically a clutch of 2-4 eggs to a

nest) and baby birds, however, are in danger

from many predators including opossum, stoat,

ferrets, rats and both feral and domestic cats.

However, unlike the wingless kiwi, the tui can

put up a delightfully strong defence.

Fortunately, effective predator control in

various regions around the country has

resulted in an increase in tui numbers

as with kiwi.

THe VaRiaBLe Tui

Inquisitive, territorial, friendly, solitary, socia-

ble, aggressive: tui (

Prosthemadera novaesee-

landiae

) are described as all these things and

more. They are most grumpily protective when

chicks are in the nest, and also jealously guard

their territory and food sources, chasing off

other birds in speedy swoops.

Single birds will defend a defined feeding

territory but they are also known to band

together, chattering and flapping to chase

off magpies or hawks. When nearby nectar

sources quit blooming, a tui may travel 10-

20km to feed or for summer breeding.

Although the sexes are alike, the male is larger

and adults have a notch on the 8th primary

feather of their wing which is what causes

the distinctive flutter we hear as they fly by.

Another distinguishing flight pattern associated

with mating rituals is when they fly up in a

sweeping arch with a sudden swooping dive

bomb descent, with the wings held tightly

into the body. These take place between

September and October when they are also

singing high up in the trees in early morning

and late afternoon.

Of all our native wonders, the tui is surely one

of the most delightful, both a visual treat and as

music to the ear.